Table of Contents

Part 1: The Shattering – My War with Perfection

For most of my life, I was at war with my own humanity.

I didn’t call it that, of course.

I called it ambition, discipline, high standards.

I was a devout worshiper at the altar of perfection, a belief system I now realize is deeply embedded in our Western cultural D.A. We are taught that beauty lies in symmetry, that worth is measured by flawlessness, and that a life well-lived is one without cracks or blemishes.1

I built my identity on this myth of the unbroken self.

My life was a meticulously curated museum exhibit, designed to showcase a person who had it all figured O.T. Every achievement was a polished artifact, every success a carefully lit display.

My flaws, my fears, my uncertainties—these were whisked away to a dusty storeroom, never to be seen.

Worthiness, in my mind, was synonymous with being whole, unchipped, and pristine.

This relentless pursuit of an impossible ideal was exhausting.

It was a full-time job policing my own thoughts, hiding any evidence of struggle, and treating my life like a checklist of accomplishments that would, I prayed, finally prove I was enough.

But the problem with building your house on a foundation of perfection is that life, in its infinite and chaotic wisdom, always sends an earthquake.

My earthquake arrived in the form of a spectacular career implosion.

A project I had poured my soul into for two years, the one that was supposed to be my crowning achievement, didn’t just fail—it disintegrated in a very public and humiliating Way. The collapse was total.

It wasn’t just a setback; it was a fundamental shattering of the person I thought I was.

The polished artifacts of my life museum were suddenly in shards on the floor.

And as I stared at the wreckage, a terrifying silence descended.

The identity I had so carefully constructed was gone.

All that was left was this feeling of being utterly, irrevocably broken.

This brokenness felt like a profound source of shame.

It was, as researcher Dr. Brené Brown describes, the intensely painful feeling of believing I was so flawed that I was unworthy of love and belonging.2

It was the fear of disconnection—that if people saw the real, shattered me, they would turn away in disgust.3

My immediate instinct was to hide the damage, to sweep the pieces under the rug and pretend it never happened.

In the aftermath, I turned to the self-help industry for a quick fix.

I was desperate for a blueprint to put myself back together, to become that shiny, unbroken person again.

I tried it all.

I chanted positive affirmations in the mirror that felt like lies.

I was bombarded with messages about “resilience,” which I interpreted as a command to “bounce back” immediately, to show no sign of injury.

This pressure to perform resilience without actually processing the pain was immense.

I glorified busyness, filling every waking moment with frantic activity to avoid the gaping hole inside me.4

But none of it worked.

The standard advice felt hollow because it refused to acknowledge the fundamental truth of my situation: I was broken.

And by trying to skip over that fact, I was denying my own reality.

The positive thinking felt like papering over a structural crack.

The relentless push for resilience felt like being told to run a marathon on a broken leg.

These solutions failed because they didn’t honor the break.

They offered no wisdom for what to do with the pieces.

They only offered shame for having them in the first place.

I was stuck, surrounded by the shards of my former life, with no idea how to build something new from the ruins.

Part 2: The Epiphany – Discovering the Art of Golden Repair

My turning point didn’t come from a bestselling self-help book or a motivational seminar.

It arrived quietly, late one night, through the glow of a computer screen.

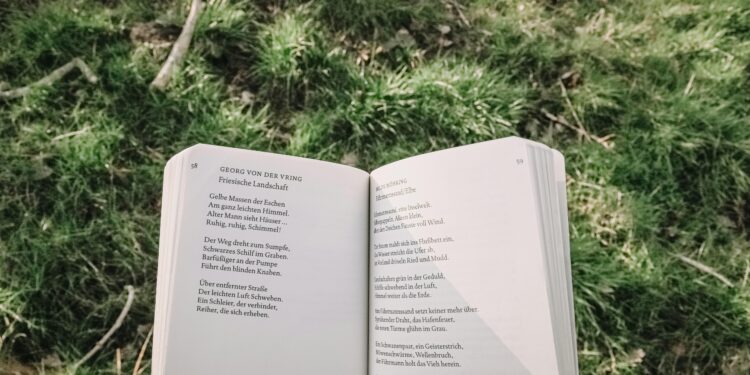

I stumbled upon an image of a ceramic bowl, crisscrossed with what looked like veins of pure gold.

It was beautiful, not in spite of its cracks, but because of them.

The caption read: Kintsugi.

I fell down a rabbit hole of research.

Kintsugi, or “golden joinery,” is the centuries-old Japanese art of mending broken pottery with a special lacquer mixed with powdered gold, silver, or platinum.5

Instead of trying to hide the repair, Kintsugi makes the lines of breakage a central, celebrated feature of the object.

The philosophy treats the breakage and repair as part of the object’s unique history, something to be honored rather than disguised.1

I was captivated.

This idea was so radically different from my own impulse to hide my damage.

Here was a tradition that didn’t just fix what was broken; it illuminated it, transforming it into a source of strength and beauty.7

The origin story of the art form resonated with me on a profound level.

It is said that Kintsugi began in the 15th century when the Japanese shogun, Ashikaga Yoshimasa, broke his favorite Chinese tea bowl.8

He sent it back to China for repair, and it was returned to him held together with ugly metal staples.

The bowl was functional, but its beauty was compromised, its history scarred by a crude and artless fix.

The shogun, deeply dissatisfied, commanded his own craftsmen to find a more aesthetically pleasing method of repair.

From this desire, the art of Kintsugi was born.1

Reading this story, I felt a jolt of recognition.

The shogun’s ugly, stapled bowl was a perfect metaphor for what I had been trying to do to myself.

I was trying to “staple” myself back together—to become functional again, to hold my shape, to get back to work.

But I was ignoring the soul of the work, which was not just to fix, but to heal.

Healing, as Kintsugi so beautifully demonstrates, is a process that honors the wound.

It integrates the story of the break into the whole, creating something new, something arguably more valuable and resilient than the original.

The shogun didn’t want his bowl erased; he wanted its journey memorialized in gold.

This was my epiphany.

What if I could apply this philosophy to my own life? What if my cracks—my failure, my shame, my heartbreak—were not flaws to be hidden, but a history to be illuminated? This question shifted everything.

It offered a new paradigm, a framework for self-love that was not about achieving perfection, but about the courageous and beautiful art of repair.

This philosophy, I learned, grows from the fertile soil of wabi-sabi, the broader Japanese worldview that finds beauty in things that are imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete.4

Wabi-sabi is an acceptance of the natural cycle of growth and decay, a stark contrast to the Western obsession with eternal, flawless youth.1

It is the wisdom to see the beauty in a moss-covered stone, a frayed edge, or a lovingly repaired bowl.

Suddenly, I had a map.

I could see that the process of Kintsugi offered a step-by-step guide for psychological and emotional healing.

It was a physical manifestation of the journey from brokenness to a new, more profound kind of wholeness.

It integrated the wisdom of ancient philosophy with the most powerful concepts from modern psychology.

I began to structure this new understanding, creating a framework that would guide my own repair.

Table 1: The Kintsugi-Inspired Framework for Self-Love

| Kintsugi Stage | Psychological Principle | Core Question for Self-Reflection | Key Thinker(s) |

| Gathering the Shards | Radical Acceptance | Can I acknowledge the reality of this pain and these broken pieces without judgment or resistance? | Marsha Linehan |

| Applying the Golden Lacquer | Self-Compassion | How can I treat myself with kindness, recognize my shared humanity, and mindfully hold my pain? | Kristin Neff |

| Curing the Gold Seams | Vulnerability & Authenticity | Do I have the courage to let my repaired self be seen, with all its unique history and golden scars? | Brené Brown |

| The Final Masterpiece | Post-Traumatic Growth | In what ways am I stronger, wiser, and more appreciative of life because of what I have overcome? | Tedeschi & Calhoun |

This framework became my guide.

It was a way to stop fighting my brokenness and instead, begin the slow, patient, and loving work of golden repair.

Part 3: Pillar 1 – Radical Acceptance: Gathering the Shards with a Gentle Hand

The first step in the art of Kintsugi is perhaps the most difficult.

Before any mending can begin, the artisan must meticulously and patiently gather every single shard of the broken vessel.

Nothing can be ignored or discarded.

This act of gathering the pieces, in all their sharp-edged reality, is the physical embodiment of the psychological principle of Radical Acceptance.

For so long, my life had been defined by a war with reality.

I was trapped in a cycle of “shoulds” and “should nots.” My career should not have failed.

I should be stronger.

This constant fighting, this refusal to accept the facts of my situation, was the source of my deepest misery.

I was introduced to the work of Dr. Marsha Linehan, a psychologist who developed Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT).

She makes a crucial distinction: Pain is an unavoidable part of life, but suffering is optional.12

Her powerful equation clarified my experience: Suffering = Pain x Resistance.13

The initial break was painful, yes.

But the true suffering came from my relentless resistance to the fact that it had happened.

Radical Acceptance is the practice of seeing and accepting reality for exactly what it is, without judgment.13

This was a terrifying concept for me at first, because I, like many, confused acceptance with approval or resignation.

I thought if I “accepted” my failure, it meant I was condoning it, that I was giving up.

A powerful clarification from DBT literature helped me understand this distinction.

Imagine a woman in an abusive relationship.

If she doesn’t radically accept the reality of her situation, she might tell herself stories to soften the truth: “He’s a good man when he isn’t drinking,” or “It’s not that bad.” These are forms of non-acceptance.

Radically accepting the fact that she is in an abusive relationship is not the same as approving of the abuse.

On the contrary, it is the only solid ground from which she can begin to make a change.14

Acceptance is the prerequisite for action.

You cannot fix a car if you refuse to accept that it is broken.

Applying this to my own life was transformative.

Radically accepting that I had failed wasn’t saying failure was good.

It was simply acknowledging the truth.

It was the only possible starting point from which I could learn, heal, and rebuild.

This process felt like a form of forensic honesty.

A Kintsugi master must find every piece, no matter how small or seemingly insignificant, to create a true and whole repair.

Similarly, Radical Acceptance required me to conduct a fearless and honest inventory of my reality.

It meant I had to stop telling myself comforting lies and instead, face the unvarnished facts of my situation.

This wasn’t a passive surrender; it was an active and courageous investigation into the truth.

I began to practice the skills of Radical Acceptance in small ways.

- I started by simply observing my non-acceptance. I noticed every time my mind used the word “should” or asked “Why me?” as a sign that I was fighting reality.15

- I would remind myself, gently, that the unpleasant reality is just as it is, and that it has causes, even if I don’t like them or understand them.12

- I practiced acceptance with my whole body. I would turn my palms up in a posture of “willing hands,” a physical gesture that signals to the brain a willingness to receive reality as it is, rather than fighting it with clenched fists.15

This was the slow, painstaking work of gathering my own shards.

Each moment of acceptance was like finding another piece of myself.

It was painful, but it was real.

For the first time, instead of trying to run from the wreckage, I was sitting with it, learning its contours, and preparing for the first, delicate touch of repair.

Part 4: Pillar 2 – Self-Compassion: Mending the Breaks with Liquid Gold

Once all the shards are gathered, the Kintsugi artisan begins the delicate process of mending.

They don’t use a quick-drying superglue.

They use urushi, a natural lacquer derived from the sap of a Japanese tree.7

This lacquer is a powerful, patient adhesive.

It is mixed with fine powdered gold, which transforms the scar of the break into a vein of beauty.5

This potent mixture—the binding lacquer and the illuminating gold—is a perfect metaphor for Self-Compassion.

My old way of dealing with my flaws was self-criticism.

My inner voice was a relentless drill sergeant, pushing me, shaming me, and telling me I was never good enough.

But Kintsugi taught me that you cannot heal a fragile piece of pottery by screaming at it.

You must handle it with care.

This led me to the work of Dr. Kristin Neff, a researcher who has defined a practical, three-part framework for self-compassion.16

This framework became my recipe for mixing my own golden lacquer.

Component 1: Self-Kindness (The Gentle Application)

The first component is self-kindness.

This means treating yourself with the same care, support, and understanding that you would offer to a dear friend in a similar situation.16

Instead of harsh judgment, you offer warmth.

I began to practice this with a simple but profound exercise Dr. Neff recommends: writing a self-compassionate letter.

When my inner critic would start its tirade, I would stop and write a letter to myself from the perspective of an unconditionally loving friend.

What would that friend say about my struggle? They wouldn’t call me a failure; they would remind me of my courage, acknowledge my pain, and express their unwavering belief in me.

This practice was the gentle, careful application of the first layer of lacquer to the raw, broken edges of my psyche.18

Component 2: Common Humanity (The Universal Truth of Breakage)

The second ingredient in the golden lacquer is the recognition of our common humanity.

This is the understanding that suffering, failure, and imperfection are not isolating personal defects, but are part of the shared human experience.16

All humans are mortal, vulnerable, and imperfect.

For so long, I had felt that my failure was a unique and shameful stain on me alone.

But the Kintsugi philosophy reminded me that all pottery is, by its very nature, breakable.

My break was not a sign of a uniquely flawed vessel; it was simply the nature of being a vessel.

This insight was a powerful antidote to shame.

I started using a simple mantra in moments of pain: “This is a moment of suffering.

Suffering is a part of life.

I am not alone in this.”.16

This realization mixed the strengthening gold into the lacquer, reminding me that my personal story of breakage connected me to everyone, rather than separating me from them.

Component 3: Mindfulness (The Patient Curing Process)

The final component is mindfulness.

Kintsugi is not a fast process.

The urushi lacquer must be applied in thin layers, and it can take weeks or even months for it to cure and harden properly.1

This long curing period requires patience and watchful waiting.

This is mindfulness: holding our pain and our healing process in balanced, non-judgmental awareness.

It means being with our difficult emotions without becoming them, and without trying to push them away.16

I practiced this using the “STOP” technique:

Stop what I was doing.

Take a deep breath.

Observe my thoughts and feelings without judgment.

And Proceed with kindness towards myself.16

This allowed me to “hold the pieces together” as they healed, giving the golden lacquer of self-compassion the time it needed to set.

It is crucial to understand that this process is not always pleasant.

Self-compassion is not about forcing good feelings.

In fact, sometimes, when you first open the door of your heart to kindness, a torrent of old, unaddressed pain can rush O.T. Researchers call this phenomenon “backdraft,” like when a firefighter opens a door to a burning building and the flames roar O.T.18

I experienced this firsthand.

The first time I truly tried to be kind to myself, I was met with a tidal wave of all the years of self-criticism and grief I had suppressed.

It was overwhelming.

But the Kintsugi metaphor held me steady.

I understood that this was part of the process.

The lacquer has to fill the empty spaces, and sometimes that means displacing the painful air that has been trapped in the cracks for a long time.

This understanding allowed me to be patient, to know that healing is not linear, and to trust that the golden lacquer was slowly, surely, doing its binding work.

Part 5: Pillar 3 – Authenticity & Vulnerability: Living with Your Golden Seams on Display

The Kintsugi piece is now mended.

The lacquer has cured, and the shards are bonded into a new whole.

But the art is not yet complete.

The final, crucial stage is to polish the golden seams, to make them shine, to transform the evidence of the break into the object’s most beautiful and compelling feature.

This final act is not one of concealment, but of revelation.

It is the physical embodiment of vulnerability and authenticity.

This is where the work of Dr. Brené Brown became my guide.

For years, I had believed that vulnerability was a weakness to be overcome.

But her research revealed the opposite: vulnerability—the willingness to show up and be seen when we have no control over the outcome—is the birthplace of joy, creativity, belonging, and love.2

It is our most accurate measure of courage.

The goal of Kintsugi is not to create an object that looks like it was never broken.

The goal is to create something that openly and beautifully tells the story of its own resilience.

This is the courage to be imperfect.3

Living a Kintsugi life meant I had to let go of who I thought I was supposed to be—that perfect, unbroken, flawless person.

In its place, I had to embrace who I truly was: a person with a history, a person with scars, a person with golden repairs.

This, Brown explains, is the heart of authenticity: the choice to let our true selves be seen.2

I began to understand the immense cost of hiding my seams.

In my quest for perfection, I had been numbing my vulnerability.

I was terrified of feeling shame, fear, and disappointment.

But, as Brown warns, we cannot selectively numb emotion.

When we numb the painful feelings, we inevitably numb the positive ones too.

When you numb vulnerability, you numb joy.

When you numb grief, you numb gratitude.

When you numb fear, you numb connection.3

My old life, in its desperate attempt to appear perfect, had been emotionally beige.

By refusing to risk the pain of being seen as broken, I had forfeited the profound joy of being seen as whole.

The final stage of the Kintsugi process, the polishing of the gold, can be seen as the intentional act of choosing vulnerability.

It’s a deliberate choice to make the history of the break more visible, not less.

It transforms the repair from a simple fact into a feature of profound beauty.

This is what it means to live authentically.

It is to have what Brown calls the courage to tell the story of who you are with your whole heart—a definition derived from the Latin root of courage, cor, meaning heart.3

A Kintsugi pot does this visually.

Its golden lines are its story, etched for all to see.

My work was now to learn to live in the same way, to have the courage to embody my own story, golden seams and all.

It was the choice to stop hiding and start shining.

Part 6: The Result – Post-Traumatic Growth: A Masterpiece More Valuable Than the Original

There is a profound outcome to the Kintsugi process that goes beyond simple repair.

The finished piece is not just “as good as new.” It is often considered more beautiful, more interesting, and more valuable than it was before it was ever broken.8

The break, and the loving repair, have added a new layer of depth and history.

This is not just resilience; this is transformation.

This concept is mirrored in the psychological phenomenon of Post-Traumatic Growth (PTG).

Coined by psychologists Richard Tedeschi and Lawrence Calhoun, PTG describes the positive psychological changes that people can experience after a struggle with adversity.22

It’s important to distinguish this from resilience.

Resilience is the ability to bounce back to your original state after a challenge.

PTG, on the other hand, is about being fundamentally changed for the better

by the struggle.

A pot that is simply glued back together is resilient.

A Kintsugi pot has experienced post-traumatic growth.22

I realized I didn’t want to bounce back to who I was before my career imploded.

That person was brittle, anxious, and built on a fragile foundation.

I wanted to become someone new, someone forged and mended with gold.

Crucially, the research is clear that growth does not come from the traumatic event itself.

It comes from the agonizing struggle to make sense of it.23

This insight is the ultimate validation of the Kintsugi framework.

The framework

is the structured struggle.

It is the deliberate, artful process of gathering the shards (Radical Acceptance), mending them with gold (Self-Compassion), and polishing the seams (Vulnerability).

PTG is the natural, emergent property of this intentional work.

The trauma is the shattering event; the Kintsugi is the meaning-making process that leads to growth.

Tedeschi and Calhoun identified five key areas where this growth occurs.22

As I reflected on my own journey, I could see each of these five domains shining in my own life, like the polished golden seams on a finished masterpiece.

- New Possibilities in Life: The complete shattering of my old career path was devastating, but it also cleared the ground for something new to grow. It forced me to re-evaluate what I truly wanted, not what I thought I should want. I discovered a new path that was more aligned with my values and my authentic self, a possibility that never would have existed had my old life not broken apart.

- Deeper Relationships with Others: My old, perfect facade kept people at a safe distance. It was impossible to truly connect with someone when I was hiding so much of myself. My willingness to be vulnerable about my struggles, to show my golden seams, allowed for a depth of connection I had never known. My relationships became more authentic, more empathetic, and infinitely more meaningful.

- A Greater Appreciation for Life: Having stared into the abyss of losing what I thought was everything, I developed a profound new appreciation for life itself. The grand, performative joys I used to chase were replaced by a quiet gratitude for simple, everyday moments—a cup of tea, a conversation with a friend, the feeling of solid ground beneath my feet.

- Greater Personal Strength: Before, I lived in constant fear of the smallest crack appearing in my perfect life. Now, I have a quiet, unshakable knowledge that I can survive breakage. I have been shattered and have learned the art of putting myself back together. That knowledge imparts a deep sense of personal strength that is far more robust than the brittle confidence I used to have.

- Spiritual Change: My old belief system, based on the worship of perfection, was destroyed. In its place, I developed a new “spiritual” framework for my life, though not in a religious sense. It is a spirituality rooted in the Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi and Kintsugi—a worldview that finds grace in imperfection, sees wisdom in scars, and understands that the most beautiful things in life are often those that have been broken and lovingly repaired.22

I was no longer the person I was.

I hadn’t just been fixed.

I had been remade.

The break was no longer a source of shame; it was the origin story of my strength, my compassion, and my capacity for joy.

Part 7: Conclusion – Living a Kintsugi Life

My journey began with a shattering—a painful collapse of the person I thought I was supposed to be.

I was lost in a culture that taught me to see my broken pieces as a source of shame, something to be hidden or discarded.

My epiphany came not from striving for an impossible perfection, but from discovering an ancient art form that offered a radically different path: the path of golden repair.

The philosophy of Kintsugi gave me a new paradigm for self-love.

It taught me that the goal is not to avoid the inevitable cracks and breaks of a human life, but to learn how to mend them with grace, courage, and compassion.

It provided a framework to transform my deepest wounds into my greatest strengths.

- By Gathering the Shards with Radical Acceptance, I learned to stop fighting reality and start working with it.

- By Applying the Golden Lacquer of Self-Compassion, I learned to treat myself with the kindness I had always reserved for others.

- By Displaying my Golden Seams with Vulnerability and Authenticity, I learned that true connection comes from the courage to be seen in my beautiful imperfection.

- And through this entire process, I discovered Post-Traumatic Growth, realizing that I was not just repaired, but had become stronger, wiser, and more whole because I had been broken.

This journey has taught me that we are all the artisans of our own lives.

We hold the pieces, the lacquer, and the gold.

Life will inevitably hand us moments that shatter our sense of self.

The question is not whether we will break, but how we will choose to mend.

I invite you to look at your own cracks, not with fear, but with the gentle curiosity of a Kintsugi master.

See the stories they tell.

See the history they hold.

You are not flawed.

You are not a failure.

You are a vessel carrying a unique and precious story.

Pick up your pieces.

Mix your lacquer with gold.

Tell your story with your whole, repaired heart.

You are not broken.

You are a masterpiece in the making.

Works cited

- Kintsugi: the art and philosophy, from broken to beautiful …, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.tedxmelbourne.com/blog/kintsugi-the-art-and-philosophy-from-broken-to-beautiful

- Embracing Vulnerability and Authenticity: A Summary of Brené Brown’s The Gifts of Imperfection – Robin Evan Willis, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.counsellingwithrobin.com/post/embracing-vulnerability-and-authenticity-an-summary-of-brene-brown-s-the-gifts-of-imperfection

- The Power of Vulnerability by Brene Brown (Transcript), accessed August 9, 2025, https://fs.blog/great-talks/power-vulnerability-brene-brown/

- The Wabi Sabi Lifestyle: How to Accept Imperfection in Life, accessed August 9, 2025, https://positivepsychology.com/wabi-sabi-lifestyle/

- Kintsugi – Wikipedia, accessed August 9, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kintsugi

- The Connection Between Wabi-sabi and Kintsugi – KonMari, accessed August 9, 2025, https://konmari.com/wabi-sabi-and-the-art-of-kintsugi/

- The Art of Kintsugi Pottery: Japan’s Golden Repair – Sakuraco, accessed August 9, 2025, https://sakura.co/blog/the-art-of-kintsugi-pottery-japans-golden-repair

- The Philosophy of Kintsugi, accessed August 9, 2025, https://kintsugi-kit.com/blogs/tsugu-tsugu-columns/philosophy-of-kintsugi

- Kintsugi | History, Pottery, & Facts – Britannica, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/art/kintsugi-ceramics

- Kintsugi Meaning & Philosophy: Finding Resilience in Life’s Cracks – Millennium Gallery JP, accessed August 9, 2025, https://millenniumgalleryjp.com/en-ca/blogs/journal/the-art-of-resilience-kintsugis-meaning-and-philosophy

- Wabi-Sabi: The Japanese Art of Finding the Beauty in Imperfections – Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.carnegielibrary.org/staff-picks/wabi-sabi-the-japanese-art-of-finding-the-beauty-in-imperfections/

- 10 Steps of Radical Acceptance | DBT Skills – HopeWay, accessed August 9, 2025, https://hopeway.org/blog/radical-acceptance

- The Healing Power of Radical Acceptance | Psychology Today, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/being-your-best-self/202203/the-healing-power-of-radical-acceptance

- Marsha Linehan on Radical Acceptance – Byron Clinic, accessed August 9, 2025, https://byronclinic.com/marsha-linehan-radical-acceptance/

- Radical Acceptance – YouTube, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwNnG7mIu1E

- The 3 Elements of Self-Compassion, According to Kristin Neff – Self …, accessed August 9, 2025, https://selfcompassionacademy.com/kristin-neff-self-compassion/

- Exploring the Meaning of Self-Compassion and Its Importance, accessed August 9, 2025, https://self-compassion.org/what-is-self-compassion/

- Self-Compassion Practices: Cultivate Inner Peace and Joy, accessed August 9, 2025, https://self-compassion.org/self-compassion-practices/

- Kintsugi Art – A Metaphor For Healing And Transformation | Insight Timer, accessed August 9, 2025, https://insighttimer.com/meditation-courses/kintsugi-art-a-metaphor-for-healing-and-transformation

- Dare to Lead | Authenticity is a collection of choices that we have to make every day., accessed August 9, 2025, https://brenebrown.com/art/authenticity-is-a-collection-of-choices/

- The Art of Kintsugi: A Precious Metaphor for the Wounded Healer – Full Circle Counseling, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.fullcirclecounseling.com/blog/the-art-of-kintsugi-a-precious-metaphor-for-the-wounded-healer

- Growth after trauma – American Psychological Association, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.apa.org/monitor/2016/11/growth-trauma

- Posttraumatic growth | EBSCO Research Starters, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/social-sciences-and-humanities/posttraumatic-growth

- Post-Traumatic Growth | Psychology Today, accessed August 9, 2025, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/post-traumatic-growth